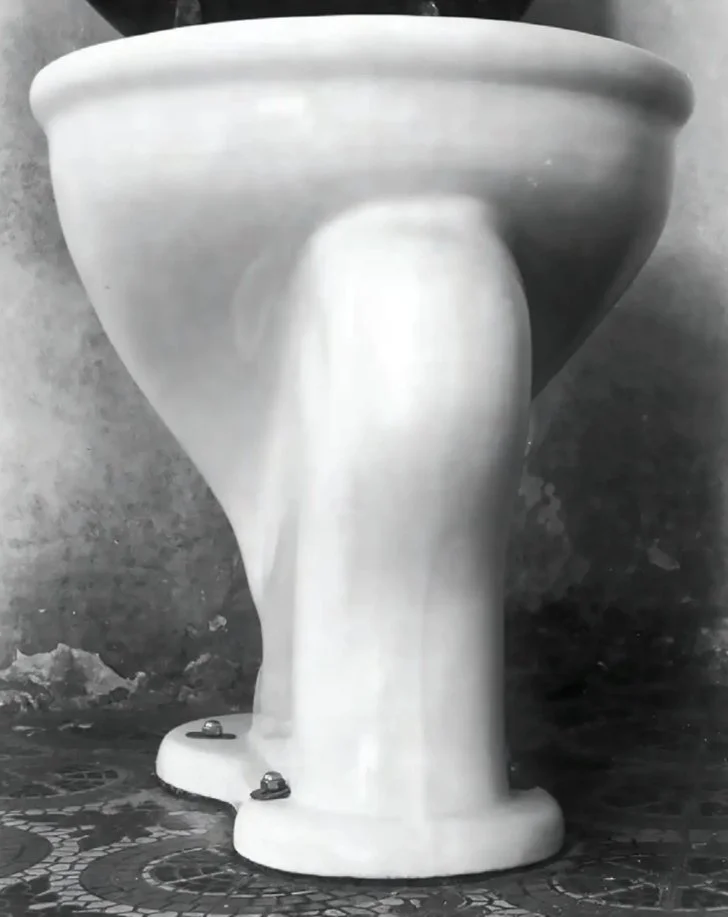

Excusado (Toilet), 1925, Edward Weston

The power of Edward Weston’s photography lies not in what he photographed, but in how consistently he saw. Across subjects that could hardly be more different—a human nude, a nautilus shell, a porcelain toilet—Weston applied the same visual discipline. Each image becomes an exploration of mass, curve, surface and light. Seen together, they reveal a single way of thinking about form.

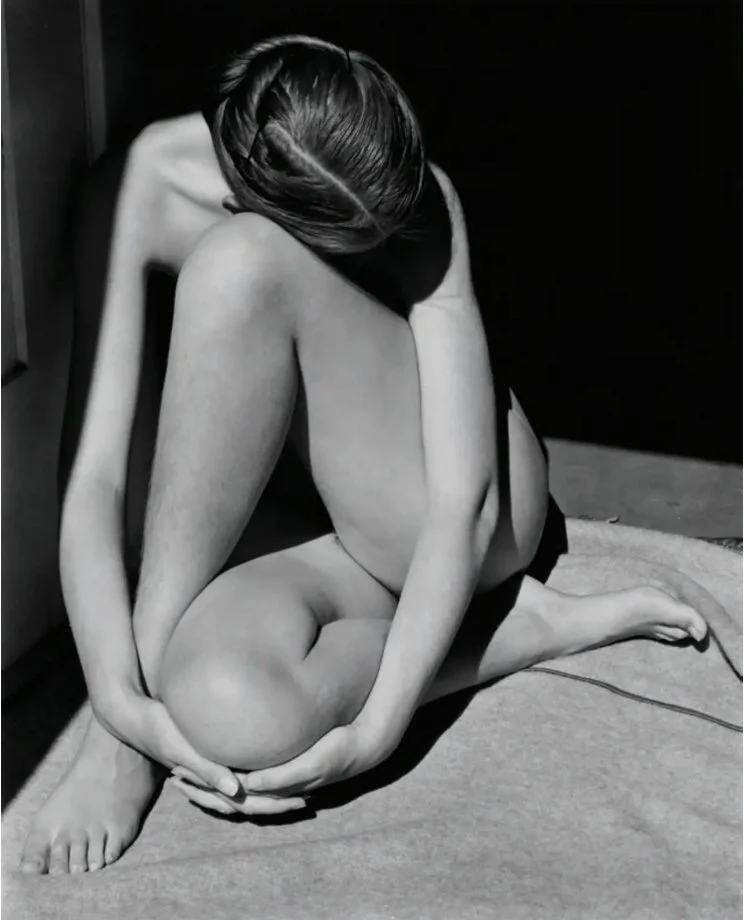

The Human Form as Sculpture

Weston’s nudes are never portraits. The image included here—head bowed, limbs folded inward—denies individuality in favour of structure. The body curls into itself, creating a closed, almost architectural volume. Arms echo thighs; shoulder flows into knee; the figure becomes a self-contained object.

The body reduced to structure: folded, self-contained, and described by light rather than identity.

Light is not used to flatter but to describe. Highlights skim along bone and muscle, while shadows carve negative space between limbs. The human body is treated as sculpture, not symbol. It is neither erotic nor narrative. Weston is not photographing a person, but a form that happens to be human.

This approach is central to Weston’s modernism: the belief that photography should reveal the essential structure of the world, stripped of sentiment and anecdote.

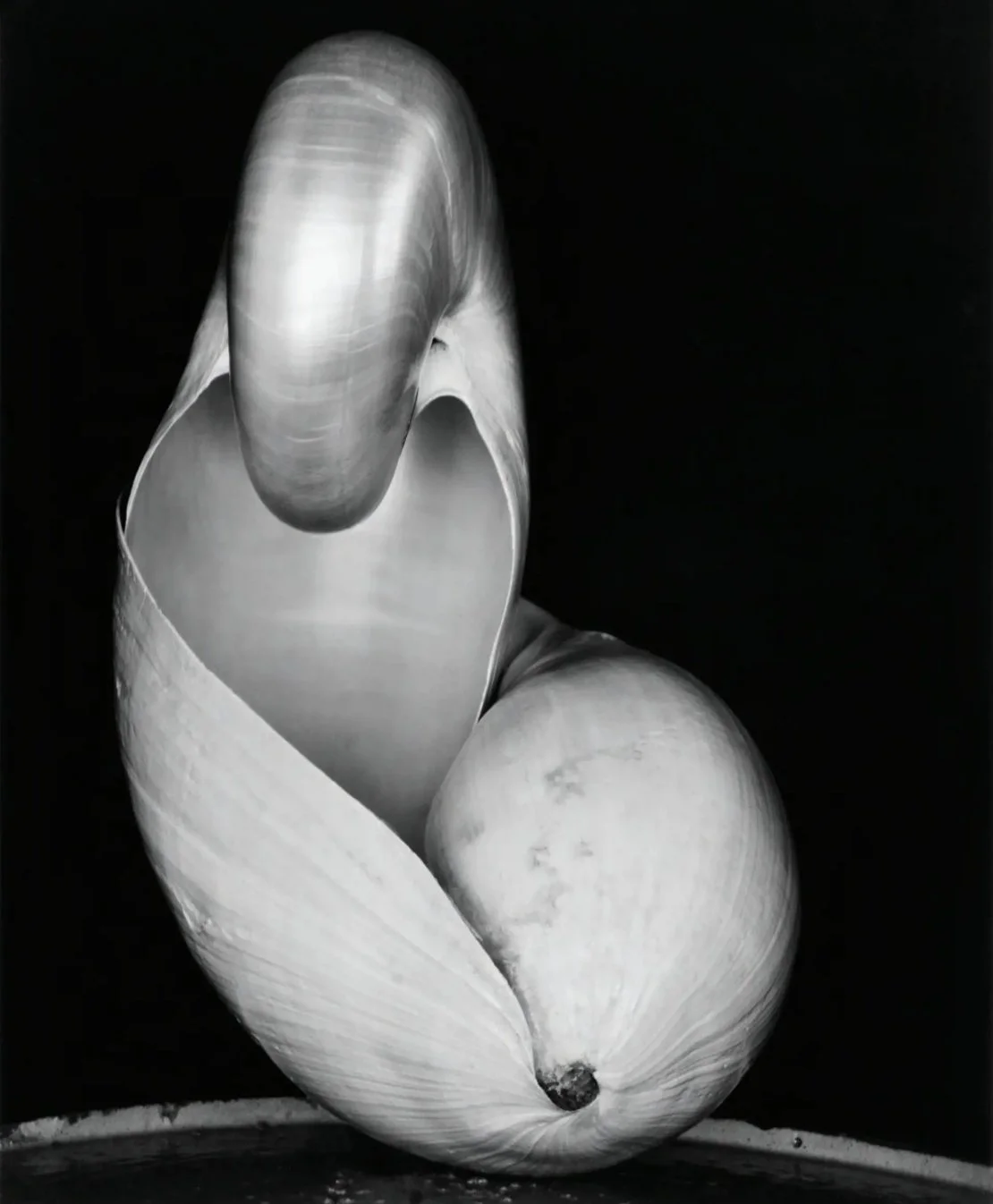

Organic Perfection: The Shell

An organic spiral rendered as pure form, where surface and volume resolve into balance.

The shell image extends this logic into the natural world. Long recognised as one of Weston’s most iconic subjects, the shell is presented as a perfect orchestration of curves. Its spiral suggests movement, but the photograph arrests it into stillness. Texture is rendered with extraordinary restraint—enough to describe surface, never enough to distract from shape.

What matters is not that the shell once housed a living creature, but that it embodies organic logic made visible. The shell folds inward and outward simultaneously, enclosing space while projecting volume. It mirrors the curled human figure with uncanny precision: both are compact, balanced, and self-sufficient.

Placed alongside the nude, the shell does not resemble the body—it behaves like it. Weston is not making metaphor; he is revealing equivalence.

The Manufactured Object: A Toilet Reconsidered

A functional object stripped of context and seen as sculpture—mass, curve and tone alone.

The toilet image, initially jarring, completes the sequence. Like the nude and the shell, it is centrally placed, carefully lit, and isolated from context. Function is suppressed. What remains is form.

The pedestal rises with the solidity of a leg or torso. The bowl flares outward, its rim echoing the curves found in both body and shell. Porcelain, under Weston’s light, loses its industrial coldness and acquires a strange, bodily presence. Subtle tonal transitions soften the surface until it becomes ambiguous—neither wholly hard nor entirely inert.

This is not provocation for its own sake. Weston photographs the toilet with the same seriousness he brings to the nude and the shell. In doing so, he collapses the hierarchy of subjects entirely. The manufactured object is granted the same visual dignity as nature and the human body.

Seeing Without Prejudice

Taken together, these three images form a single argument. Weston’s achievement was not in finding beauty in unlikely places, but in refusing to rank subjects at all. Beauty, for him, emerged from clarity of seeing.

Each image is controlled, deliberate, and previsualised. Backgrounds are suppressed. Composition is stable. Light is descriptive rather than dramatic. Nothing is accidental. Whether the subject is flesh, calcium, or porcelain is irrelevant once it is reduced to form.

This is why the toilet belongs beside the nude and the shell. Not as a joke, nor as a challenge to taste, but as proof of consistency. Weston’s camera does not judge. It isolates, examines, and reveals.

Conclusion

Seen in isolation, each of these photographs is compelling. Seen together, they clarify Weston’s vision. The human body, the organic shell, and the industrial object are not opposites but variations on a single theme: form revealed through attention.

Weston did not photograph things for what they meant. He photographed them for what they were. And when seen with sufficient care, each—body, shell, or toilet—becomes complete, sufficient, and strangely inevitable.